One of the best parts of this job is spotlighting key community members who ensure we have access to recreational land and the wildlife it supports. Meet Andrew Ortiz, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Andrew took the time to let us get to know him a little better. Thanks for your time Andrew.

Jay Pinsky, Editor - The Hunting Wire

Q: Andrew, where did your curiosity in wildlife and hunting come from?

A: From my dad and uncles on our farm in southern Colorado, thirty minutes from prime elk habitat. We ran sheep up in the mountains. We hunted elk, deer, and upland birds in Colorado and New Mexico. I remember putting garbage bags in my boots so my feet would not get wet from the snow when I was a boy. We wore blue jeans and flannel shirts. My dad taught me how to shoot and field dress game, and we hung deer and elk for jerky. I think this is funny; my dad told stories of throwing clays off the deck of the USS Jupiter for his captain during the Korean War. He unknowingly planted a germ of an idea, and today I compete in amateur trap and sporting clays.

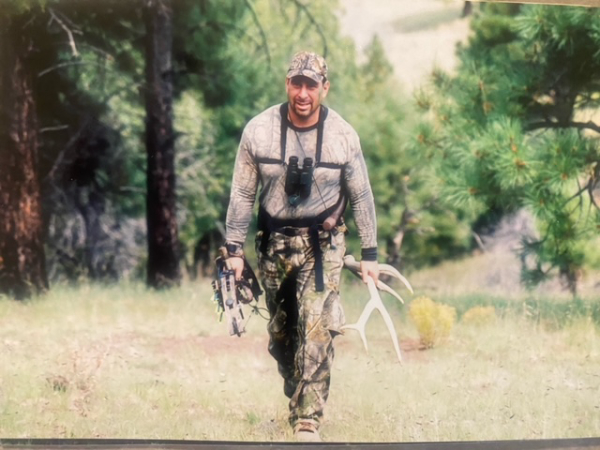

Q: What prompted your interest in bowhunting and archery?

A: My roommate and teammate, Tim Rizek, at New Mexico State University, where I earned a degree in Wildlife Science, introduced me to bow hunting—and I was hooked from the get-go. My first job after graduation was in the field, and it was a great start, but it did not pay me much. My teammate’s dad helped me purchase my first bow. I am still grateful. He was inadvertently practicing what we call today R3: recruitment, retention, and reactivation. He was making sure a young man had the means to enjoy nature and the outdoors better.

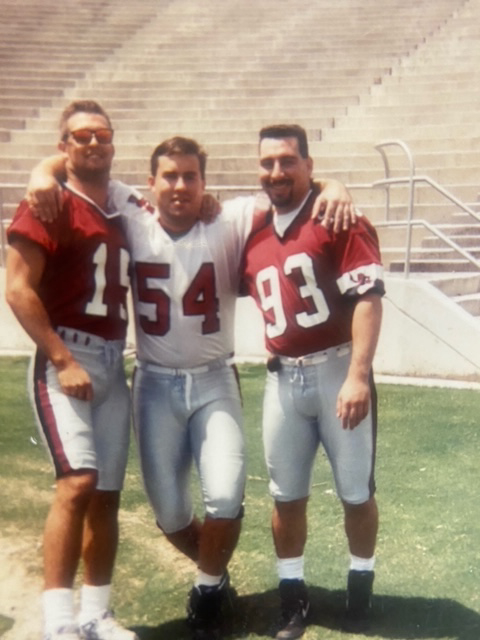

Q: You played football at New Mexico State; how did that inform your future?

A: Playing D-1 football for the Aggies was a dream come true. I was an outside linebacker. I learned to stare adversity in the face—and I mean that figuratively and literally. One game stands out: in 1989, we lost to Oklahoma University at Norman, 73 to 3. The Sooners were among the top-ranked teams in the country. When you have a pulling guard at 300 pounds trying to block you and me at 250, you must adjust, get low and stop him. It was the toughest loss, and I still have OU turf in my facemask from that epic day that sits in my office.

Football taught me never to give up and keep my goals high. Persevere. Football, hunting, and conservation have this in common: you invest or train today for a better outcome in the future. All these years later, I still train to get into shape for bow hunting. The Gila National Forest is my favorite place to hunt elk in New Mexico, and you need to be in top shape to have a chance at harvesting a trophy bull no matter where you go. And I still hunt with my Aggie teammate—Tim is one of the best elk callers I know.

Q: So, how are archery and conservation intertwined?

A: Regulated hunting is, of course, one tool in the quiver of wildlife management, like prescribed burns and silviculture, food plots, and so forth. Pittman-Robertson dollars make all that happen—an 11-percent excise tax paid by makers of firearms, ammunition, bows, and some accessories are the currency of conservation. Those monies and hunting license fees fuel the science-based work of the state fish and wildlife agencies. State wildlife agencies use the money to buy needed equipment and to purchase habitats. Pittman-Robertson also funds the construction and operation of target shooting ranges—for firearms and archery parks—where hunters and recreational shooters have a reliable, safe, and organized place to practice or compete.

The amount of Pittman-Robertson dollars going to the four-state area where I work is not insignificant. In 2023, the Arizona Game and Fish Department got $34.1 million; New Mexico Department of Game and Fish, $24.6 million; Oklahoma Department of Wildlife Conservation, $28.9 million; and Texas Parks and Wildlife, $55.1 million. All told the states and territories received $1.2 billion nationwide this year, all derived from the manufacturers.

Q: Do you happen to have any recent target range examples?

A: The Ben Avery Range in Arizona is a gem, the largest of its kind in the U.S. The IDEA Public Schools/Camp Rio Archery Park opened on three acres a year ago near Brownville, Texas, and will serve 6,000 students and other community members annually. I managed the Pittman-Robertson grant with the Oklahoma Department of Wildlife Conservation for the new shooting range complex at Oklahoma Panhandle State University, open to the college students and faculty and the larger Goodwell, Oklahoma, community. Closer to home, I worked at the Stephen M. Bush Memorial Shooting Range in rural Clayton, New Mexico. This was unique; Mrs. Bush donated the land to the New Mexico Department of Game and Fish to develop a shooting range to honor her husband. These are only a few of the nearly 850 public ranges in the U.S.

Q: Any tips on bows or hunting for our readers?

A: Bows are like trucks—there are many brands to choose from that get the job done. Because bowhunting is so special to me, I upgrade about every five years. As for ensuring success—that’s like football. Put in the work today for your physical health tomorrow, and scout your hunt in advance. Lastly, practice R3 yourself; that too is an investment in the future.