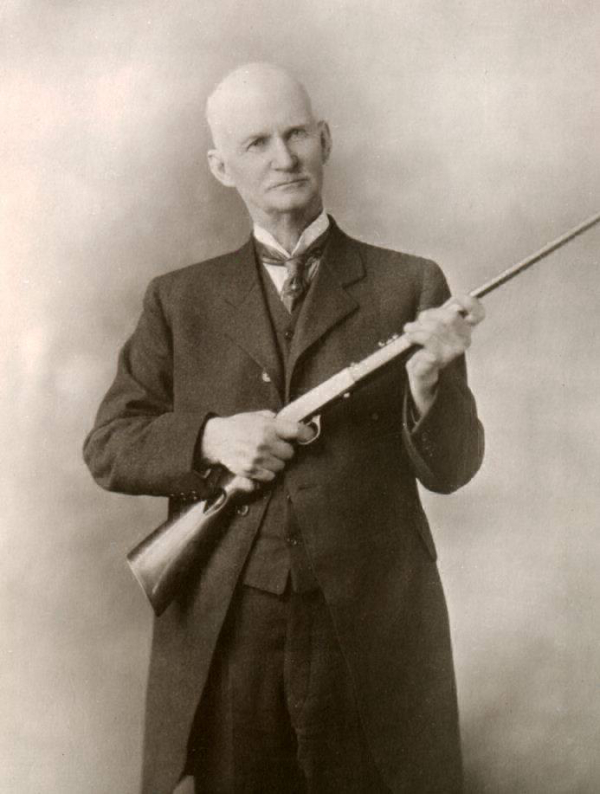

When most people think of John Moses Browning, they envision a man bound by tradition. He is the father of the classic lever-action, the guiding hand behind firearms that fit perfectly in walnut and blued steel. We put him on a pedestal, a Rockwell portrait in steel.

The truth is, Browning wasn’t simply a traditionalist. He was an innovator who constantly pushed the boundaries, and this spirit of continual improvement forms the heart of his legacy, even today.

He didn’t preserve history; he dissected it, tinkered with it, and filed over 100 patents, proving that there’s always a smarter way. Today, he’d be first at the range, torque wrench in hand, logging group sizes, capturing data in an app.

Every lever-action we prize started life as somebody’s wild experiment. When John Moses Browning designed the 1886, he wasn’t chasing nostalgia. He was cranking out horsepower. That dual-locking lug action was muscle in steel, built to tame the larger, hotter cartridges Winchester wanted to chamber. It was the big-block engine of its day, strong, reliable, and begging to be tuned.

Fast forward to 1935. Winchester engineers looked at Browning’s 1886 frame and decided to build something meaner, sleeker, faster. Enter the Model 71. They re-profiled the action, shaved weight, and chambered it in a new cartridge, the .348 Winchester. That round was no mild cruiser; it was a supercharged load built to hammer elk, moose, and bear. The 71 wasn’t just a rifle, it was a hot rod born out of Browning’s original blueprint. Same bones, new fire.

Like any good hot rod, the Model 71 wasn’t cheap, and it wasn’t built for everyone. It was for the hunters who wanted more, more reach, more knockdown, more steel in their hands. The 1886 was the chassis; the 71 was the custom build that ran faster, hit harder, and looked good doing it.

And if Browning were here today? I’d hand him a .30-30 with a red dot for fast work in thick timber, or a .45-70 with a modern LPVO to stretch the range. He’d grin that quiet grin and say what every hot-rodder thinks when someone bolts on a better carburetor or swaps in a bigger engine: “We should’ve done this sooner.”

Browning’s geek credentials were undeniable. Obsessed with detail, he sketched designs on scraps of paper in his father’s shop and chased ideas relentlessly. An unfaltering experimenter, he worked with Winchester, Colt, Remington, FN, and Savage, never confining himself to one company or style: innovation outweighed loyalty. A true rule breaker, at the turn of the 20th century, when few imagined a recoil-operated shotgun, Browning didn’t just dream it, he built it.

Lever-action purists’ recoil at mounting optics. For Browning, optics were just another tool. He always sought ways to make firearms faster, tougher, and more effective. The once-radical lever-action was as disruptive as today’s AR-15. What’s old-fashioned now was cutting-edge in the 1880s. Just as Browning adapted the lever gun for bigger cartridges, he’d adapt it again for today’s hunters, with optics.

The heart of the matter isn’t about whether putting a red dot on a lever gun is disrespectful to Browning; it’s about whether clinging to nostalgia contradicts the progress-driven mindset that defined his work.

Browning’s life was about breaking molds and finding solutions. He reinvented tradition, not worshiped it. Insisting his designs never change misses the point.

When I mounted a red dot on my Browning Model 71 carbine, I wasn’t erasing history. I was carrying it forward, just as Browning did, taking a proven platform and pushing it into the future.

Let’s be honest: The real risk is refusing to evolve. Browning never stood still. Why should we?

Browning wasn’t a curator of the past; he was an engineer of the future. If he saw a Marlin 1895 with a scout scope or a Henry X with a red dot, he wouldn’t sneer. He’d shoulder it, grin, and ask about glass clarity, mount torque, and parallax at 100 yards.

That’s the lever-action spirit: always improving, always innovating, always looking forward. In 2025, the most John Browning thing you can do might be to bolt on a good optic and ask, “What’s next?”

Jay Pinsky - Editor, The Hunting Wire & Archery Wire

jay@theoutdoorwire.com