There are two ways to hunt elk: you go to them, or they come to you. The first is astoundingly aerobic. The second is just as punishing, but in a quieter way. It doesn’t test your legs; it tests your mind.

I’d tried the first way a few times, burning boot leather across big country, lungs on fire, chasing bugles that always seemed one ridge farther than they sounded. I came home empty. Not discouraged, just honest enough to admit I was open to a different approach.

I just didn’t know how different it could be.

When Fred Eichler, owner of Full Draw Outfitters in Aguilar, Colorado, tells elk hunters they’ll need to sit, really sit, in a blind for days and nights on end, most assume he’s joking. He isn’t. When Fred says you’re living in a blind, he means it literally: you eat there, sleep there, and wait there. You don’t step outside to stretch, walk off a cramp, or crack the door for fresh air. You don’t scroll your phone, tap your feet, or sigh just to hear yourself make a sound.

You don’t move.

The only call you’re allowed to answer is the one from Mother Nature, and for that, you get two garbage bags, a roll of toilet paper, and the silent blessing of every hunter who came before you and did whatever it took to punch a tag.

Long before I stepped into the blind, I’d been preparing for this hunt through a year of study in The Lever Gun Chronicles. My rifle of choice turned heads, a Smith & Wesson lever gun. To most, it seemed an odd pick from a company better known for wheel guns and semiautos. But if you know lever gun history, you know Smith & Wesson is a historically appropriate choice for the rifle you carry on a hunt. To those who’ve paid attention, it made perfect sense, and in the field, it proved exactly why.

Most people don’t realize Smith & Wesson’s lever-action roots run deep. They didn’t invent the lever gun; that credit belongs to Walter Hunt and his 1848 Volition Repeating Rifle, but Horace Smith and Daniel B. Wesson shaped its evolution. In 1854, they produced one of the first commercially successful lever-operated firearms: the Volcanic pistol. Its toggle link system became the foundation for the Henry rifle, which evolved into the Winchesters that defined the American West.

When Smith & Wesson returned to lever actions with the Model 1854, they weren’t stepping into new territory; they were stepping back into their own history.

Better yet, that rifle was about to become more than historical to me. It was about to become personal.

The rifle I brought into that blind wasn’t a family heirloom or a safe queen. It wasn’t a nostalgic nod to the past or some romantic cowboy showpiece. It was a working rifle, a stainless-steel Smith & Wesson Model 1854 chambered in .45 70 Government, and it had a job to do. I chose it deliberately.

Before the hunt, I polled every elk hunter I respected, and a few I didn’t, about which 1854 chambering to trust: the mule-kicking .45-70 or America’s whitetail darling, the .30-30 Winchester.

No one picked the little guy. So, I didn’t either.

I spent months driving the 1854 hard before Colorado. From day one, it ran like it had something to prove, slick, tight, no grind, no quit. The rifle didn’t ask for care; it demanded respect. Stainless steel, built for blood and weather, not glass cases.

I fed the 1854 Hornady 250-grain MonoFlex ammunition from the Leverevolution line, the Grand Island crew’s love letter to lever gun hunters and topped it with a Trijicon Accupoint 1-6x24mm optic. At 50 yards, the rifle grouped sub-MOA; stretched to 200 yards, it still held MOE, or Minute of Elk.

I didn’t come to Colorado to play cowboy. I came to kill an elk. My first bull. And the 1854 was coming with me because it had proven something most people don’t want to admit:

A lever gun isn’t a limitation. A lever gun is a choice.

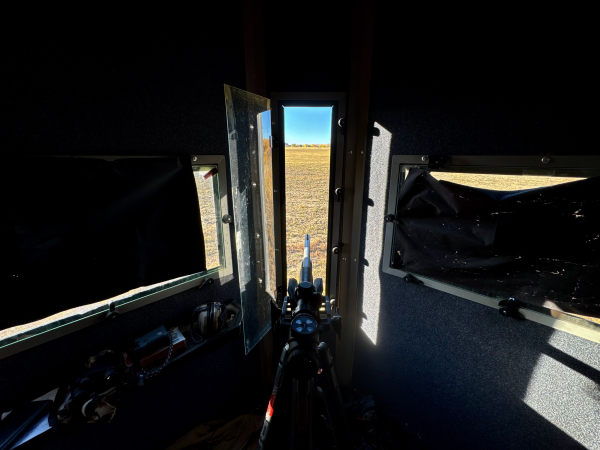

The first night in the blind taught me that silence has a sound, a low hum of my heartbeat and the faint rasp of nylon when I breathed too deeply. Sleep came in fragments. The cold pushed through everything: the blind, the sleeping bag, and eventually, my thoughts. You don’t touch your phone. You don’t crack a light. You don’t move. Out there, the dark feels alive. Every sound, a branch snapping, a coyote calling, the soft scuff of hooves on frost, arrives like a question you’re not sure you want to answer.

I kept the 1854 beside me. I knew where it was in the darkness above all else. And if Fred’s forecast proved right, I’d need it first and fast.

Dawn came. The elk didn’t.

Around noon, guide Blye Chadwick released me from my blind. I headed back to the clubhouse unfazed but thankful for indoor plumbing. After a hearty lunch, a shower, and a mattress-inspired nap, Fred and his team sent me back to the same blind for round two.

What a difference a day makes.

At 4 a.m., a bull bugled so close I thought he’d tip the blind over. Legal light was still hours away, but a danger-close bugle woke you up in ways coffee never could. I doubt I blinked until first light, and when it came, I blinked often, because the sunrise revealed not one elk, but hundreds. After years of elk slipping past me, this was the moment I’d chased in my head a thousand times. But there was no time to smell the wapiti roses. The dreaming part was over.

The closest cluster stood 350 yards out, plenty close for some, not for a man with a .45-70. I needed them, and specifically a bull, a lot closer.

Right on cue, a bull erupted from the brush, bugling, herding cows, and charging directly toward me.

I eased my rifle from the open front window to the closed side window, lifting it in slow motion. Through the Vortex Fury LRF binoculars, I ranged him: 138 yards. I steadied the rifle, peered through the Trijicon, and waited. Two cows, one in front and one behind, shielded him. The back cow moved. Then the front. Then the bull turned, head-on. It’s a shot plenty of hunters take. I didn’t.

When he finally turned broadside, I centered the tritium-lit triangle behind his left shoulder and squeezed the trigger.

BOOM.

The rifle erupted. The blind shook. For a second, I saw only the ceiling. Then I looked where he’d stood, and he wasn’t there.

I scanned left. About 50 elk stood 200 yards away, all looking left, except one. My bull. He was looking right, wobbling like a tired lumberjack refusing to quit. I got back on him and waited. A cow walked up, tilted her head as if to ask, What’s wrong with you? Then she turned away.

BOOM.

Second shot: 180 yards, quartering away, the 250-grain MonoFlex driving behind the right ribcage and across his chest. His front legs buckled, but he didn’t fall.

BOOM.

The third monolithic finally sent him crashing into the alfalfa field once and for all.

The first shot killed my elk.

The third shot convinced him.

Soon, the sound of trucks and voices crested the ridge. Smith & Wesson’s Joe Vega was first to congratulate me, followed by Blye Chadwick, Mark Land, and Fred Eichler. Everyone celebrated; it was a team win.

Field prep followed. The bull’s weight was honest, the work heavier than the excitement that came before it. We took photos, then a tractor lifted the bull onto a flatbed for the hanging pole. Knives replaced cameras, and the day turned to labor.

Back at camp, stories began to unfold. Preston Lentfer from Hornady had taken his first bull that same morning, 298 yards with his 1854 in .30-30 Winchester. Vincent Perreault, Smith & Wesson’s Director of Marketing, tagged his first bull on day three at 40 yards, also with a .30-30. Both men ran Hornady’s 140-grain MonoFlex.

When we’d all tagged out, Vincent and I finally sat long enough to talk about the rifle. Listening to him, I realized the 1854 wasn’t a gimmick or a nostalgic cash grab; it was a return to something real.

“When we built the 1854, we didn’t look backward,” Perreault said. “We built it to prove the lever action still belongs in the field.”

The idea, he explained, started with a simple hallway conversation.

“There was a void. Marlins weren’t moving yet under Ruger; Henry was carrying the space alone, and we knew hunters wanted options, real ones. That’s when someone said, ‘Why not us?’”

Once the decision was made, momentum followed.

“Once we committed, nobody flinched,” Perreault said. “Engineering, manufacturing, design, everyone knew this rifle had to be more than nostalgic. It had to hunt. Hard.”

He emphasized that the 1854 had to honor its roots while fixing the weaknesses of old designs.

“We focused on end users first, hunters. That means smoother cycling, modern optics compatibility, better ergonomics in cold weather, and reliability you don’t have to baby.”

The receivers, he noted, are forged in the same facility that builds S&W revolvers.

“We don’t just stamp parts, we forge them. There’s a difference you can feel the first time you run the lever.”

While some brands sell rifles for display, Smith & Wesson built one for work.

“We didn’t overthink it,” he said. “People still hunt. They still want rifles with soul. The lever gun isn’t dead; it just needed to evolve.”

Looking at my rifle, still dusted with Colorado soil, I couldn’t disagree.

The first shot killed my elk.

The third shot convinced him.

And somewhere between the two, the Smith & Wesson 1854 convinced me.

— Jay Pinsky

jay@theoutdoorwire.com